And heres to you Monsieur Roubo. Few workbench designs can be as bulletproof and as simple as the ones by A.J. Roubo was an 18th-century cabinetmaker and a talented writer.

An 18th-century French workbench is quite possibly the most perfect design ever put to paper.

It was not unusual for the living and work areas to be in the same room in the 18th century. A workbench, for example, would not be out of place in the front room of the house.

This small historical fact has me concocting a plan, which I havent yet shared with my family.

My workshop is located in my basement. Although I have done my best to make it comfortable, it is still isolated from the rest. This is intentional: My jointer and planer sound like air-raid sirens.

During the brutal stock-preparation phase of a project, my shop is perfect. I can run machinery all day and bother no one. When I am involved in the joinery of a project I long for a shop that has beams of natural lighting, wooden floors, and close connections to my daily life.

Also, I would like to use the upstairs space as a bench area.

Keep calm: This story doesn’t just concern me. Its about you, too. A furniture-grade workbench is a great idea for apartment dwellers, or people who need to set up a shop in a spare bedroom of their house. Its also a fine idea for people like me who plan (read: plan to grovel for permission) to do some woodworking in a living area of their home.

Lucky for us all, the most beautiful workbench design is also the easiest to build and the most useful.

Thank You, Monsieur Roubu

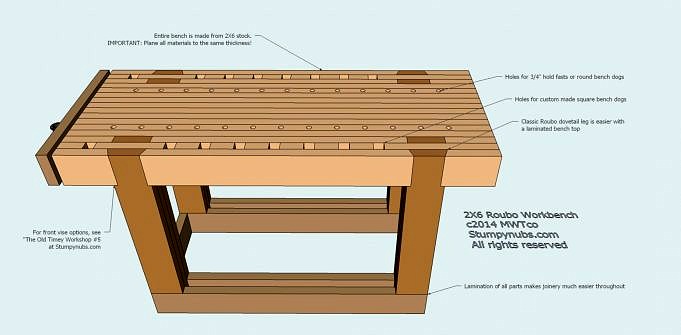

Over the past five years, I have built or helped to build more than a dozen workbenches that were based on the 18th century designs of Andr J. Rubo, a French cabinetmaker. And after five years of working on Roubos bench I think it is an ideal bench with almost none of the downsides or limitations Ive found on other forms.

Its advantages are numerous. Here are a few.

1. Its simple design makes it easy and quick to build, even for beginners.

2. The thick slab top has no aprons around it, making it easy to clamp anything anywhere on it (this feature cannot be overstated).

3. The front legs and stretchers are flush to the front edge of the benchtop, making it easy to work on the edges of long boards or assemblies, such as doors.

4. It is heavy due to its massive parts. The bench is stable and won’t move or rack as you work.

But what about its looks? The first Roubo-style workbench I built was out of Southern yellow pine. I think it looks great, but an 8-long pine behemoth might be best suited to the workbench underworld. And it is probably too big for most living areas.

So I decided to go back to the original text for inspiration. The original bench, which was published in plate 11 in LArt du Menuisier, shows beautiful exposed joinery with through-dovetails. It also has a single piece wood as its top, something George Nakashima would be proud of (if it had some bark).

The original Roubo bench shares many similarities with Shaker furniture (thanks for its exposed joints), Arts & Crafts furniture (thanks in large part to its lack of ornamentation), and contemporary styles (thanks in large part to the clean lines and single-board top). This bench looks like a lot of furniture that contemporary woodworkers enjoy building and will look at home in the home (if youre lucky) or in the shop.

Information About The Raw Materials

The biggest challenge with this bench is finding the right raw materials, particularly for the top. I needed a slab at least 5 x 20 x 6 mm thick. Thats a tall order. If you’re interested in following the lead, here are some: Check out Craigslist.com’s building materials section. There are always old construction beams for sale. You will need to be able to find them for a reasonable price.

A local sawyer can be found (we use a Wood-mizer.com network). Of course, drying a wet slab that size will take time or some serious work in a kiln. A third option is to go to a specialty lumber supplier, such as Bark House, Spruce Pine (barkhouse.com), who specializes in large slabs of kiln dried lumber that can be shipped all over the country.

Almost any species will do for a workbench. I would choose maple or ash as my first choice, but most species are strong enough and sturdy enough to be used as a benchtop for boards between 4 and 5. I ended up with two slabs of cherry that were donated by housewright Ron Herman of Columbus, Ohio. Although they had some blemishes and checks, I was confident that I could turn them into a nice-looking top.

As long as the undercarriage looks nice with the top, you can use almost any material. I used construction-grade 26 white pine for the stretchers and 66 mystery wood for the legs. I built the project almost entirely with hand tools (except for a couple long rips). This was just for fun. Your definition of fun may vary. All of the techniques here easily translate to a power-tool shop, so dont be put off by the joinery; just fire up your band saw.

One other thing to note: You dont need a workbench to build a bench. The entire bench was made on sawhorses, without any help from the benches or vises in the shop.

Face your edge. You should treat each edge as if it were a face when you join two large slabs together to make a benchtop. This means that you need to check the surface for flatness across its length and width. Take your time.

I began the project by dressing the two rough cherry slabs so I could join their edges to make my benchtop. Thats where well pick up the story.

Take The Tool To The Work

One out of one editors agree. This is a terrible idea. Even with my coarsest ripsaw, this slab was too much. After sweating for 20 minutes, I finally ripped the edge with my band saw. A pitsaw, pitsaw and a strong friend are the best tools for this job.

The length and the width of your top will determine the rest of the design of the bench. Here are a couple pointers: Make your benchtop as long as feasible, but it doesnt have to be wide (in fact, wide workbenches are a liability in many cases). My experience shows that a 51 cm wide bench is sufficient to be stable and large.

Straight up. You can save a ton of work for yourself by checking the slab to ensure it will be flat when its glued up. A wooden straightedge is ideal for this operation.

One seam was required to connect the middle of my benchtop. To dress the edges I removed the sawmill marks with a jack plane, then dressed each edge with a jointer plane. Running these edges over the powered jointer would be a two-man job. You can do this by hand by yourself.

Once you get the two edges flat, rest them on top of each other. Make sure to check for any gaps in the seams and then use a straightedge or a ruler to make sure they form a flat slab. No matter which brand of glue you choose, glue the top to the surface and allow it to rest overnight. You want the glue to reach maximum strength and you want most of the water in the glue to evaporate (if you use a water-based glue).

More than one way to cut a board. Handsaws are designed to be held in a variety of positions, including this one. This position uses different muscles than when you are cutting with the teeth facing the floor. Trying different positions will prevent you from tiring out as quickly.

Once the slab is joined, you can dress its outside edges once more using handplanes. This is less work than lifting it over your machines manually. After you dress the first edge, make the second one nearly parallel. Then cut the benchtop to length.

I used a 7-point crosscut handsaw. Although it was hard work, it was very easy.

With the top cut to finished size, dress the benchtop and underside so they are reasonably flat and parallel. Do a good job here because this will be the working surface youll be using to make the remainder of your bench. Flatness will save you from future struggles.

Start flattening your top by using traversing strokes along the grain with your Jack plane. Follow that up with diagonal strokes with a jointer plane. For the truly lucky, you can run the slab through a wide-belt sander. No matter what method you use, make sure to inspect the top for twist.

It is best to install your end vise first before you start cutting the legs. That way you can use that vise to cut all the joints on the legs. I added a large wooden chop to a vintage quick release vise. This will allow the benchtop to support large panels.

Simple and small. My end vise was a vintage quick-release vise of 18 cm. It’s possible to use any vise, even one you already have.

In addition to the vise, you also should drill the dog holes in the top that line up with the end vise. If you are using joinery planes that have fences, such as rabbet and plow planes, place the holes near the front edge. The center of the holes was placed 1 m from the front edge. Place them evenly and closely. Don’t forget to mark where the through-tenons and though-dovetails will be. You dont want to put a hole where the joint will go. My holes were placed on four centers. You’ll be fine if you can get them closer to the center (say, 3).

The Magical Mystery Legs

Accuracy at a low price. I use aluminum angle as winding sticks. These parts are cheap, super-accurate and dont lose their truth unless you abuse them. To make it easier to see the twist, paint one end of each one black.

I have no idea what species of wood these legs are. They were 66 timbers and I found them at the back of my home centre. They were slightly wet with a few green streaks resembling poplar. They were tough, stringy and difficult to plane. They were inexpensive and looked good. I also didn’t need to glue any stock to make thick legs.

With your crosscut handsaw, cut them to rough length (1-inches). Your workbench’s height will be determined by the length of your legs. There are many ways to determine your ideal workbench height. My favorite technique is to measure from the floor up to where your pinky joint meets your hand. For me, that measurement is about 34.

If you use hand tools, I would err on the side of a bench thats a little too low rather than too high. Low benches are ideal for handplaning and let you use your leg muscles as much as your arm muscles. Your jack and jointer planes can be used to dress the legs. Next, prepare to lay the joinery.

Measure, but not trace. Each leg will have a different layout. So trace the joint layout onto the top to get a real idea of the waste you need to remove.

The joints in the legs and top are unusual each leg has a sliding dovetail and a tenon. Why did Roubo use a sliding dovetail and not a twin-tenon? I don’t know. I don’t know. However, I believe the sliding dovetail makes it easier to cut the joint and prevents the part from twisting due to the sloped walls.

I spent a couple days you read that right), poring over Roubos drawings and the translated French text to lay out the joints so they were balanced and looked like the joints shown in the 18th-century text. I wont bore you with the details (like I bored my spouse), so heres what you need to know:

Each sliding dovetail is 1 in thick and the tenon 1 in between. The remainder of the joint is a shoulder on the inside face of the leg. The dovetail is sloped at 1 to 1 (about 30). Thats steep, but it looks right compared to Roubos drawings and other early French benches Ive examined.

Almost an instant tenon. Leave the tenons way overlong. Theyll be mitered to size after you excavate your mortises.

Lay out the joints. Be sure to make them about overlong so you can cut them flush with the benchtop after assembly. Then fetch your biggest tenon saw and a large ripsaw.

It’s big, but not too large. You can define the cheeks as best you can with a tenonsaw by making diagonal cuts. You can also use a well-tuned, band saw to do this. You can’t go further with your tenon-saw, it is time to get the big boy.

Connect two. After sawing cheeks across the entire width of the legs, this is easy work. Take your time. Fixing a wandering dovetail slope is no fun.

Begin by cutting the inside cheek to get warmed up its easiest to fix this joint if you go off line. Start with your tenonsaw (mine is a 16-inch model with 10 points). Start by kerfing the end grain at the top. Next, cut diagonally one side of the cheek. Turn the leg around and cut diagonally again. Then remove the V-shaped waste between.

Connect two. After sawing cheeks across the entire width of the legs, this is easy work. Take your time. It is not fun to fix a wandering dovetail curve.

When the top of your joint hits the saws back, switch to a rip-filed handsaw to finish the job. Now do the other cheek of the tenon the same way. Next, follow up by completing the inside dovetail.

The diagonal drill. This is a large angled tenon cheek. Kerf in the top of the joint about 120 cm deep. Then saw diagonally down until you hit your baseline and the far corner of the benchtop. Next, turn your attention to the opposite side of the benchtop.

Cut the dovetail slopes at the corners of each leg. Start with the tenon and end with the rasp. The dovetail can be cut in the same way as the tenon. Kerf in the ends grain a little. Next, work diagonally along both edges to remove any stuff in between the diagonal cuts.

Heavy metal. A heavy mallet (1 kg. will make the work go faster. Here Im almost halfway through the second side and the waste is starting to come loose. Pry it out as soon as its feasible.

For looks alone. To the end of my vise-chop, I added a square oval shape. The bench doesn’t serve any purpose other than to look like furniture. Cut the shoulders of the ovolo with a backsaw. You can use a bowsaw or file to cut the curve.

I tried many ways to get rid of the material between the dovetail tenon. I found the fastest way to remove the waste was to use a mortising tool chisel.

Even a coarser one took longer to saw it out using a bowsaw. You can use a bowsaw to blitz out the waste. Start at your baseline and chisel down. Then chisel in diagonally about 1 away from that first cut to meet your first cut. Pop out this V-shaped piece of waste. Continue until you are halfway through. Continue flipping the leg and doing the same on the other side.

Clean the canyon from the dovetail to the tenon. A paring chisel makes short work of flattening the bottom.

Then cut the shoulders of the legs. You have three shoulders to cut: Two are up front at the base of the dovetail and the third is at the inside of the leg. I used a crosscut sash saw to make this cut. A smaller carcase saw also would do, but it is slower.

The Difficult Females

Side-splitting fun. Remove as much of the waste as possible by splitting it off the sides. Wood splits easily along its grain. Knowing the woods weakness is always a big advantage.

The through-mortises are some work. You won’t have (or want) to use a 1-inch mortising chisel. Instead, take a leaf from the timber framers. To excavate the mortise, you will need to remove the bulk of the debris. Then clean up the walls with a mortising chisel (at the ends) then chisel along the walls.

This is an excellent excuse to purchase a large brace. A brace with an 8-10 sweep is the most popular choice for cabinetmakers. I recommend a 12-14 sweep. This will give you more mechanical advantage. Sadly, my 12 brace went missing, so I gained a workout.

Router plane thoughts. I wish I could write a love letter to my router plane. It makes tough jobs such as this quite easy. Note you might have to remove the depth adjuster wheel on your tool to reach this depth.

Sharpen the biggest auger you have and mark the flutes so youll bore about halfway through the top. Clear the holes of waste, then use a mortising chisel to bash out the ends of the mortise (this is the hard and exacting part). Next, use a large paring chisel for separating the remaining waste from the walls. This is simple.

Something for the corners. Your router plane wont reach into the tight inside corners. So use a paring chisel. You can then use the router plane to create a flat floor and remove any junk.

Flip the bench over and bore through the other side. Clean up the mortise and ensure that the cavities meet. Humps in your mortise walls can be troubling and are quite common. Check your work with a combination square.)

Dont be shy. Split the bulk of the waste by making a few kerfs. Stay about 120 cm away from the baseline to avoid splitting away wood you want to keep.

Luckily, the dovetail socket is easy work compared to the mortise. Define the walls of the socket using a backsaw (I used a sash saw). Next, use your crosscut handsaw to make several kerfs from the waste. Use a sturdy chisel to remove the waste and clean the socket floor with a router plane.

It’s A Cheat, But Not What You Think

Boring work. Usually I use boring as a pun here. This is seriously boring work. A drill press would have been a welcome machine here though how I would have put this benchtop on the drill presss table is beyond me. Id probably move the drill press over to the benchtop and swing the table out of the way.

I made my stretchers using 26 material from the home center. After I dressed the stock (it was twisty) it ended up at 1 thick. To make it easier, I laminated two 2x6s face to face. The tenons would be the long one. The short one would be the shoulders between the legs.

Mark the tenon. Use the same 320 cm bit for boring the holes to mark their center points on the tenons. Then disassemble the joint.

A bit of truth here: Its unlikely my legs are perfectly square or their faces are parallel to one another. But if you discard your measuring systems, youll be OK.

Again, please dont measure. Hand-cut mortises and tenons are best done by direct comparison. Show the tenon to the mortise (or the mortise to the tenon) and mark what you need.

It is important that each stretcher fits perfectly between its legs, and ends up at 8 cm above the floor. This is the perfect space for your foot and will come in handy when planning across the grain.

How high? Who cares. I have clamped two battens between my legs and placed the stretcher on top of them. Now Im marking the shape of the shoulders directly on the stretcher.

From the inside. Heres what this looks like on my side of the bench. Use a knife for accuracy. Then cut your stretcher to length with a handsaw.

So I figured out where the stretchers should intersect the legs and cut two battens to length (21 long in this case). These battens were clamped to my legs. I then placed the stretcher on top of the battens, marking the length from my legs. These shoulder lines were not square, but thats no big deal if you cut them with a handsaw.

After I cut these pieces to length with a handsaw I confirmed that they fit between their legs. After I cut them to length with a handsaw, I laminated each piece to make a 26-inch section. As a result the stretchers wont have a shoulder at the back (this is called a bare-faced tenon), but that is no big deal in a bench.

Mortises That Meet

Mortise holes first. The 320 cm holes pass entirely through the legs and mortises. Be sure to stagger the holes if you are going to peg all four stretchers. If they do not, the pegs could collide.

If you make mortises inside a leg, you will have the tendency to split the inside corner of your joint when the second mortise intersects the first. Does it matter? Probably not much. However, I would love to have every bit of wood I can get.

Mortise without the mess. Here Im boring out the intersecting mortise, which is deeper than the first mortise. This results in cleaner mortise walls, and more area for glue.

So I use an old English trick for intersecting mortises. Make your first mortise shallow so it will just kiss the second (deeper) mortise. This prevents the inside corner from breaking off.

Move the bore. Shift the centerpoint toward the shoulder of the tenon. When building benches in softwood this can be about 381 cm without (much) danger.

The mortises in the legs are smaller than those in the top, but the procedure is the same. You can remove most of the waste. Get rid of the rest.

Pare the long-grain walls. You should be pretty good at this by now.

Now miter the ends of your tenons. The tenons dont have to touch you wont get any points if they do. Then show the mitered tenon to the mortise to mark out the location of the edge cheeks. Cut the shoulders and edge cheeks. Next, fit each tenon.

Mallet Time

High and dry. When the bench parts finally go together, the result is remarkably stout, even without glue.

Do a dry fit of all your parts to ensure that not only will the individual joints go together, but that all the joints will go together at the same time. You could put together the base, and then, if you’re lucky enough to get it in place with a nail or two, you could also put the benchtop in its place. But I prefer to assemble the entire thing at once.

To keep the joints together, I used drawbored pins (to hold the shoulders to the legs) as well as slow-setting epoxy. It is possible to do without glue. However, if you have the money to buy glue, there is no disadvantage.

Once the benches pieces are in place, mark the location where the -diameter pegs should go on the legs. They were placed about 1 inch from the shoulder of my tenon.

Clamps and drawbores. This might seem like wearing both a belt and suspenders, but it will reduce the number of splintered pegs.

Drawingboring is easy: Drill a hole through your mortise, assemble your joint, and mark the spot where the hole intersects with the tenon. Disassemble the joint and move the centerpoint of your hole closer or farther to the shoulder. Then drill the hole through the Tenon.

The offset holes in the peg will pull the shoulder against the leg when you drive it in. If you have drawbore pins, these metal pins will deform the holes a bit. And they let you test-fit the joint before glue or a peg gets involved in the equation.

A Pause Before Assembly

If you are going to install a leg vise, now is the time to bore the hole for the vise screw and the mortise for the parallel guide. You won’t need to detail this as it is the same as any other mortises.

There are a couple design considerations: Make the center of your vise screw about 10 or so from the top of your workbench. This will allow you to clamp 12-wide stock in the leg vise with ease. Also, you have a lot of flexibility as to where you put the parallel guide. It can be placed on the floor for maximum leverage, or above the stretchers for minimal stooping. The parallel guide doesn’t make a difference in leverage, so I would place it above the stretcher. This is easier to do.

Another design tip: Make sure your mortise is the same size as your parallel guide. A close fit reduces the amount of racking that the vises chop will do left and right. This is what I can assure you.

Big Finish

When I assemble something, I dont take chances. If I can clamp it, I will. And if I can glue it, I will (unless it will cause wood-movement problems). So I used some slow-setting epoxy, which has a practical open time of several hours. I applied glue to all the joints, knocked everything together then applied the clamps to get things as tight as possible.

Then I drove in the white oak pegs. These pegs are easy to make. You can crimp them and drive them through a dowel tray. Whittle one end so it looks like a pencil. Use paraffin to lubricate and secure the pin. The paraffin is another timber-frame trick that works well. Since I started using it Ive had far fewer exploding pegs.

Also, wedges. Roubo says to wedge any tenons protruding through the top. I declare this joint bomb-proof.

After driving your pegs, wedge the through-tenons through the top. I used 4 point wedges. For directions on how to make these wedges using a handsaw or band saw, visit popularwoodworking.com/aug10. After the glue has set, take the clamps off and saw the tops of the Tenons and the wedges to the benchtop.

True up the top again, just like you did at the beginning of the project. Next, you can focus your attention on the face vise.

Im A Leg Man

Leg vises are awesome. You can customize them for your work. You can build them in a day. They are strong and hold well. They don’t have the parallel bars iron vises use. You have more clamping space.

Why have they almost vanished? Beats me. Most people who try them love them.

Three parts make up the vise: The chop, which is what you do and which holds the work; the vise screws (usually purchased items), which move the chop in and out; along with the guide that pivots your chop against your work.

The parallel guide is the thing that trips up most people who are new to leg vises. The parallel guide is attached to the chop and moves in and out of a mortise in the leg. A pin pierces the parallel guide in one of its many holes. When the pin contacts the leg, the chop pivots toward the benchtop and clamps your work.

This is the setup. This is the setup. You can also see the hole that I cut for the vise screws. Its simpler than it sounds.

After you have cut your chop, you will need to create an orifice to hold the vise screw. The parallel guide is placed in the chop, and is pierced with two rows of holes on 1 centers. The two rows are offset with.

I know, all this sounds complicated. Its not. I built my first leg vise years ago without ever having used one. It was easy to master in 30 seconds. You will, too.

A Place For Planes

A shelf is essential. Let me repeat that: You really need a shelf. There you will keep your bench planes and any parts or tools you may need during a project. You’ll be glad that you built the shelf.

The shelf takes just a couple hours to build by hand (less if you slay electrons in your shop). Start by attaching an 11 cleat to each of the four stretchers’ bottom edges. I used glue to attach the nails. Then youll nail shiplapped shelf boards to

These cleats will create the nesting area for your bench planes.

One setup for the shelf. My shelf boards measure 3 cm thick. I set my plow plane to make a 15 cm-wide x 320 cm-deep rabbet. A minute of work on each edge made the perfect joint.

To make the shiplapped boards, use a plow plane to make the rabbets on the long edges. This is a simple task in pine. I went the extra step and beaded one long edge to dress up the boards. The two boards on the end will need to be notched at the corners to fit around the legs. You already know what you need to do.

Nail the shelf boards in place with about gap between each. A single nail in the middle of the width of each board is best.

This will stop your hard work from being taken apart.

A Simpler Finish

Finishes on workbenches should be functional, not flashy. A bench’s finish should be easy to clean, resistant to glue and stains, and not too slippery. Slick benches stink.

The answer is so easy. Mix equal parts boiled linseed oil (to resist glue), varnish (to resist spills) and paint thinner (to make it easy to apply). Use the amber liquid to shake it up and apply it by rubbing. Three coats is all you need. Once it’s dry, you can start to work.

What is work? The Pottery Barn catalog was one of the inspirations that inspired this bench. I am a bit cowed to admit this. The catalog featured a fake workbench sold to be used as a wet bar. I wondered: What if a genuine workbench was used as a sideboard, a wetbar or a table behind the couch?

You see, some people allow their workshop furniture to be made of ugly plywood, screws and crude joints. That is not how I build. When I invest my time in something, I want it to be both beautiful and functional (thank you Gustav Stickley for that line).

So whether this bench goes in the dankest dungeon or in your living room, I think you should do your best to ensure that all your work is ready for the front room of your house.